Japanese | English

– Ecological Consequences of a Distorted Trophic Pyramid and Anthropogenic Pressure –

Abstract

Encounters between humans and bears, primarily the Asiatic black bear (Ursus thibetanus), have increased across Japan in recent decades. These incidents are frequently portrayed as wildlife management failures or abnormal animal behavior. This paper argues that such encounters are instead the logical ecological consequences of long-term anthropogenic disturbance. We analyze (1) the distortion of the trophic pyramid caused by the historical loss of apex predators, (2) the inability of bears to secure biologically necessary territories, and (3) excessive human population density and land-use expansion. Using conceptual ecological models, we demonstrate that responsibility for human–bear conflict lies predominantly with human-driven ecosystem alteration.

1. Introduction

Human–bear encounters in Japan are commonly framed as sudden and unpredictable threats. However, ecological theory holds that animal behavior reflects adaptive responses to environmental constraints. When suitable habitat is lost, wildlife does not change its nature; it changes its spatial behavior.

This study reinterprets human–bear encounters as indicators of systemic ecological imbalance rather than isolated incidents. By integrating trophic structure, spatial ecology, and anthropogenic pressure, we aim to identify the structural causes underlying these conflicts.

2. Ecological Background

2.1 Collapse of the Apex Predator Tier

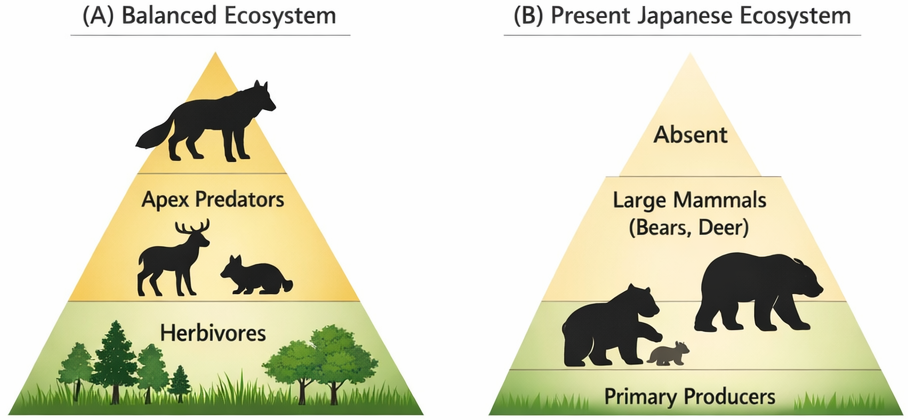

A stable ecosystem typically includes apex predators that regulate prey populations and behavior through top-down control. In Japan, apex predators such as the Japanese wolf (Canis lupus hodophilax) were exterminated during the modern era.

Conceptual comparison of a balanced trophic pyramid (A) and the current Japanese ecosystem (B), characterized by the absence of apex predators and weakened top-down regulation.

2.2 Spatial Requirements of Bears

Bears require extensive, continuous territories to access seasonally variable food resources. Their ecological strategy presupposes large, connected forest landscapes with minimal human disturbance.

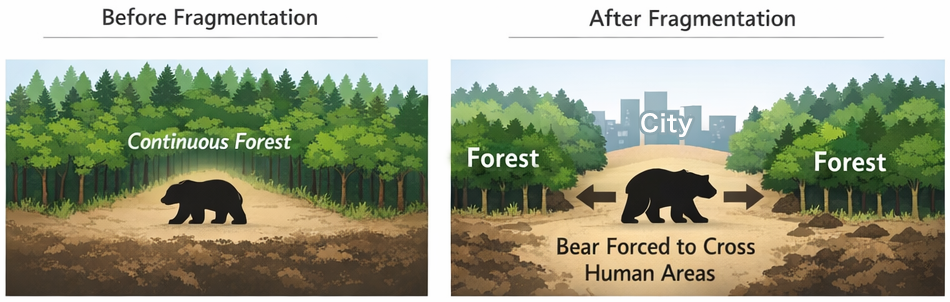

In modern Japan, however, habitat fragmentation has severely constrained bear movement and territory formation.

3. Analysis

3.1 Habitat Fragmentation and Territory Loss

Human land use—urban development, agriculture, roads, and infrastructure—has subdivided bear habitat into isolated patches. Figure 2 presents a simplified spatial model of this process.

Schematic representation of how habitat fragmentation forces bears into closer proximity with human settlements by disrupting continuous forest territory.

3.2 Human Population Density as an Ecological Stressor

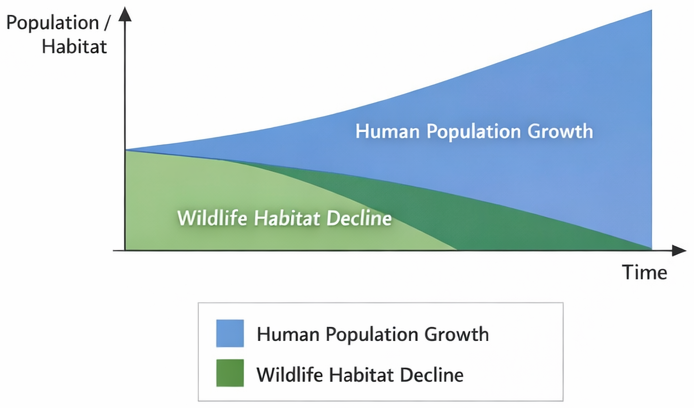

Humans differ from other species in that they expand territorially without ecological self-limitation. High population density amplifies land conversion, resource extraction, and exclusion of other species.

Conceptual model showing the inverse relationship between human spatial expansion and available wildlife habitat over time.

4. Discussion

4.1 Misinterpretation of Bear Behavior

Urban appearances of bears are frequently interpreted as abnormal or aggressive behavior. From an ecological perspective, these movements represent rational responses to spatial and nutritional constraints.

The data suggest that bears are not encroaching on human territory; rather, humans have expanded into bear territory and eliminated viable alternatives.

4.2 Which Species Is Ecologically Overabundant?

If ecological impact is used as the metric, humans represent the most disruptive species within the system. Humans:

- Occupy space without natural population control,

- Alter ecosystems at unprecedented scales,

- Remove competing species while remaining ecologically unregulated.

Bears remain functionally embedded within ecological limits.

5. Conclusion

Human–bear encounters in Japan are not anomalies but predictable outcomes of anthropogenic ecosystem distortion. The primary drivers include:

- A trophic pyramid lacking apex predators,

- Chronic loss and fragmentation of bear habitat,

- Excessive human population density and land dominance.

The responsibility for these conflicts lies overwhelmingly with human society. Long-term mitigation requires a shift away from reactive wildlife removal toward structural reconsideration of human land use and ecological responsibility.

コメント